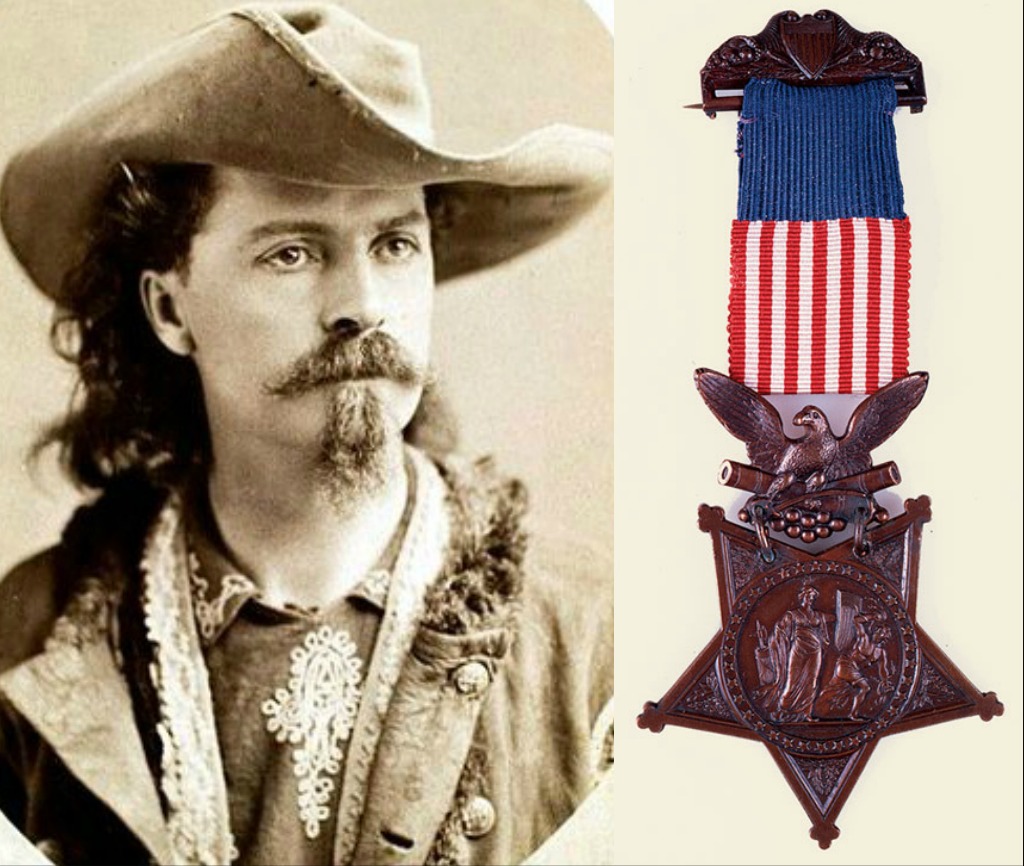

Buffalo Bill Cody and the Medal of Honor

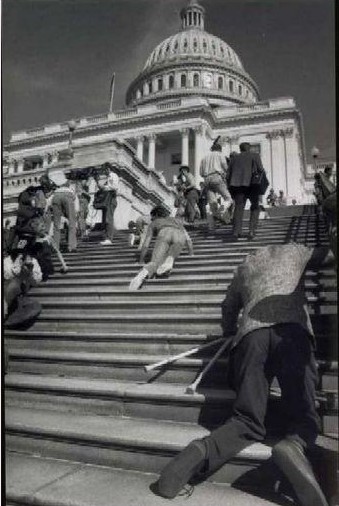

Photo Credit: Buffalo Bill Cody, ca. 1875 on left (George Eastman House) and his Congressional Medal of Honor on the right (Buffalo Bill Center of the West).

Buffalo Bill Cody’s name is deeply cemented in Wild West history. The famous frontiersman, Pony Express rider and buffalo hunter’s legendary antics were popularized (and usually exaggerated) in dime novels. His fame propelled him to created a stage show aptly named “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West” show that debuted on May 19, 1883 in Omaha, Nebraska. However, not all of Cody’s actions were sensationalized – specifically his time in the military. For his role and “gallantry in action” during the Indian Wars, Buffalo Bill Cody was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor on April 26, 1872.

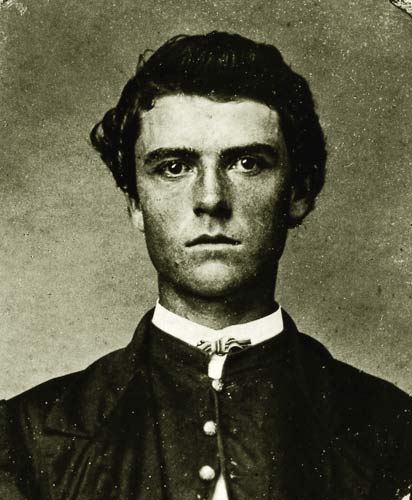

In early 1864, Cody enlisted in the 7th Kansas Cavalry, a volunteer Union regiment, and fought throughout the Civil War. After the war between the states, he was contracted as a civilian scout for the U.S. Army during the Indian Wars in the 1860s-70s. During these campaigns, Cody fought in nineteen battles and skirmishes with various American Indian tribes and was wounded once. It was during one of these face-offs that his actions made him a Medal of Honor recipient.

On April 26, 1872, while traveling along Nebraska’s Platte River near Fort McPherson, Cody showed his “gallantry in action”. He was scouting for the Third Cavalry, commanded by Captain Charles Meinhold, when he located a camp of horse-stealing enemies. In his report, Captain Meinhold described what happened next:

Mr. Cody had guided Sergeant Foley’s party with such skill that he [Foley] approached the Indian Camp within fifty yards before he was noticed. The Indians fired immediately upon Mr. Cody and Sergeant Foley. Mr. Cody killed one Indian, two others ran towards the main command and were killed.…

While this was going on Mr. Cody discovered a party of six mounted Indians and two lead horses running at full speed at a distance of about two miles down the river. I at once sent Lieutenant Lawson with Mr. Cody and fifteen men in pursuit.

He…gained a little upon them, so that they were compelled to abandon the two lead horses…but after running more than twelve miles…our jaded horses gave out and the Indians made good their escape.…Mr. William Cody’s reputation for bravery and skill as a guide is so well established that I need not say anything else but that he acted in his usual manner.

Buffalo Bill Cody at the age of 19 – around the time he served in the Civil War. Photo Credit: Buffalo Bill Historical Center

After receiving his Medal of Honor, the Buffalo Bill Historical Center noted that Cody rarely talked about it. He believed he was awarded the country’s highest honor because of his “continuous service during the Civil War, and afterwards in the Indian War” rather than the specific events of April 26, 1872. Cody could have simply been confused by the award and the fully meaning behind it since the Congressional Medal of Honor was relatively new. [The Medal of Honor was first awarded to U.S. Army honorees ten years before – in 1862.]

Cody passed away from kidney failure on January 10, 1917. A month after his death Congress revised the standards for awarding the prestigious honor. The U.S. Army revoked 911 recipients’ Medal of Honors after Congress decided that only military personnel could receive the award. Since Cody was recognized as a scout – considered civilian personnel – his medal was one that was stripped from him.

Even though his name was removed from the Medal of Honor roll, no one came to take the physical medal back. It was passed down in the Cody family before being donated to the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody, Wyoming (the town was named after Buffalo Bill). The descendants and the Buffalo Bill Historical Center banded together to get Cody’s medal reinstated. With the help of Congressman Dick Cheney, Cody’s Medal of Honor was restored on June 12, 1989 along with the medals of four other civilian scouts from the Indian Wars.

Buffalo Bill Cody’s life story has its fair share of embellishments, however, his dedication to the Union cause and later to the U.S. Army can hardly be discounted. Cody’s legend as a colorful showman, fierce Indian fighter and notable scout remains strong within the study of the American Old West. Among the long list of things he is known for, Medal of Honor recipient is one of his most prestigious titles – even if he never realized it himself!

Further Reading

Buffalo Bill Historical Center

Congressional Medal of Honor Society

“William F. ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody,” State Historical Society of Iowa.

“New Perspectives on ‘The West’: William F. Cody,” PBS.org.

“Buffalo Bill’s Medal Restored,” The New York Times, July 9, 1989.