Behind the Photo: “She Walked Alone” (Little Rock Nine)

Elizabeth Eckford, age 15, pursued by a mob at Little Rock Central High School on the first day of the school year, September 4, 1957. Photo by Will Counts/Source

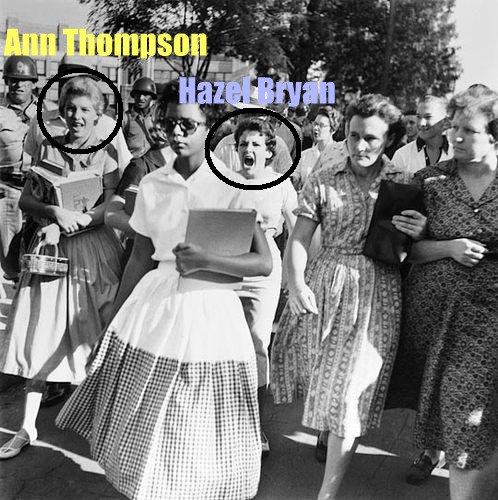

Elizabeth Eckford, Hazel Bryan and Ann Thompson were all 15-years-old students when they were immortalized on film in one of the most famous photographs from the Civil Rights Movement. The moment was captured on September 4, 1957 in Little Rock, Arkansas by Will Counts, a young photographer with the Arkansas Democrat. The photograph embodies the plight of this young girl to have the same educational opportunities as others. On the other hand, it also shows the utter anger and rage of those opposing her and the integration of the high school. As a whole, the photograph exemplifies the Civil Rights Movement – those against any changes to the status quo and those striving for basic human rights.

Ann Thompson (left circle) and Hazel Bryan among the mob that launching verbal assaults against Elizabeth Eckford, age 15, at Little Rock Central High School on the first day of the school year, September 4, 1957.

In order to understand the full meaning of the photograph, we have to delve into the integration of Little Rock Central High School and those students forever known as the “Little Rock Nine.”

On May 17, 1954, the historic Brown v. Board of Education declared that segregated schools were unconstitutional. All U.S. schools therefore needed to be desegregated. This did not sit well in the South as black students attempted to apply to all-white schools. The Little Rock School Board in Arkansas agreed to comply with the Supreme Court’s ruling. They planned to begin desegregation in September 1957. Nine students were chosen to start the process based upon their grades and promptness. These students were given the nickname “Little Rock Nine” – one of which was Elizabeth Eckford.

On September 4, 1957, the day of the school’s integration, the plan was for the nine to arrive together as a unified group. They would meet at Daisy Bates’ house as she was the director of the Arkansas chapter of the N.A.A.C.P. They would then arrive at the school and walk to the rear entrance. However, the night before, the plan changed. Since Elizabeth’s family did not have a telephone, she was not aware of the changes. So she took her planned route to school. In the morning, she got on the bus bound for downtown. Elizabeth walked the remaining few blocks to the school.

Elizabeth was the first to arrive. She was alone. A 400-person mob surrounded the school. As she walked to the front entrance, the National Guard prevented her from entering. In three different areas Elizabeth tried to enter but was denied every time by the National Guard who were under orders from Arkansas Governor Faubus. He was staunchly against the integration and ordered that the “Little Rock Nine” not be allowed into the school. By preventing Elizabeth’s entrance, Faubus defied a federal court order.

After she was turned away the last time, Elizabeth made her way to a bus stop. Around her the mob was hurling insults – even threatening to lynch her. Two of the white students in the mob and insulting Elizabeth were (Mary) Ann Thompson and Hazel Bryan. When looking at the photo, a person’s eyes naturally go to Hazel. With her short, curly dark hair and mouth twisted in rage, Hazel is the picture of hate. “Go home, nigger! Go back to Africa!” Hazel shouts incessantly.

Ann, the blonde girl with her arms laden with books, was friends with Hazel. She later recalled the scene reflected in the photograph:

I honestly can’t remember exactly when I first saw Elizabeth Eckford. Everybody was milling about and looking around, wondering which way they were going to come from. I knew immediately something was happening when the noise picked up from the parents and students. All of a sudden Elizabeth was walking down the sidewalk and there was a rush. We had to let her know that she couldn’t come to our school. So we ran up behind her and started chanting and jeering, “Two-four-six-eight. We don’t want to integrate!”

Even though she appeared to be stoic and resolute with her eyes covered by her glasses, Elizabeth was barely holding herself together. She prayed for assistance but found little when she turned to the National Guard. Besides making sure the mob did not get too close to her, they offered little support. So Elizabeth hoped to find someone among the crowd who would help her in case things took a deadly turn.

They [mob] moved closer and closer. . . . Somebody started yelling. . . . I tried to see a friendly face somewhere in the crowd – someone who maybe could help. I looked into the face of an old woman and it seemed a kind face, but when I looked at her again, she spat on me.

Elizabeth finally made her way to the bus bench and sat down. She began to cry. Benjamin Fine, a New York Times reporter with a daughter the same age, sat next to her and comforted her. He told her, “don’t let them see you cry.” He later described the ordeal: “This little girl, this tender little thing, walking with this whole mob baying at her like a pack of wolves.”

He was not the only one trying to shield her. Other reporters – Jerry Dhonau and Ray Mosely of the Arkansas Gazette and Paul Welch from Life – enclosed her in a protective circle. Grace Lorch, a white civil rights activist who had just dropped her daughter off at a nearby school, saw Elizabeth sitting on the bench. Grace stayed with Elizabeth to make sure the mob did not try to hurt the girl. To the mob, Grace asked, “Why don’t you calm down? . . . Six months from now you’ll be ashamed at what you’re doing.” Grace then went with Elizabeth on the bus and made sure she got to her mother’s workplace safely. [Because of her involvement, Grace and her family found themselves a target. Dynamite was found placed in their garage and the press would not leave them alone – call them traitors and worse. They eventually moved to Canada.]

Because of Faubus’ decision to disregard federal court orders, former Arkansas governor Sid McMath and Little Rock’s mayor Woodrow Wilson Mann asked President Dwight D. Eisenhower for help. Eisenhower, upset over the governor’s actions, federalized the National Guards – thus removing it from Faubus’ power. However, this did not stop the violence or the tension looming over Little Rock. On September 23, 1957, a mob of over 1,000 people attacked African-American reporters. While the mob’s focus was elsewhere, the Little Rock Nine entered the high school. Eisenhower saw photos of reporter L. Alex Wilson being beaten by the mob. He immediately sent some of the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock to maintain the peace and oversee the desegregation process.

Grace Lorch, standing on the left, comforting and protecting Elizabeth Eckford at the bus stop. Photo Credit: NPS

While the troops were stationed at Little Rock Central High School, they could not stop the daily insults and danger the nine were in inside the building. “Most people think it was the first day. But it was the whole year,” Elizabeth recalled. There was heckling and verbal abuse in the halls. People made passive statements, “as if I wasn’t there. Others bumped me against the lockers.” She was pushed on the stairs, punched, had things thrown at her and endured taunts and humiliating songs.

The one person Elizabeth did not have to deal with was Hazel. Of her role in the mob scene, and subsequent photo, Ann asserted that Hazel was “rather pleased with herself.” On September 6, Hazel was even talking to reporters in front of the school. She was adamant that “[w]hites should have rights, too!” Because of her role in the photograph and subsequent days talking to reporters, people could now put a face to racism. Hazel’s parents pulled her from Little Rock Central.

The press and people of Little Rock wondered which of the “Little Rock Nine” would withdraw first. Many believed Elizabeth would having been deemed the most sensitive and fragile of the group. She did not withdraw. However, neither Elizabeth or any of the “Little Rock Nine” would return to Little Rock Central High School the next school year. Faubus closed down Little Rock high schools for the 1958-1959 school years (referred to as “The Lost Year”) in retaliation for the integration.

Elizabeth, along with the other eight, ended up leaving the south. She bounced around from Missouri to Illinois then to Ohio before making her way back to Little Rock in 1963 for a visit. It was then she received the most unexpected message. Hazel wanted to talk to her.

Soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division escort the Little Rock Nine students into the all-white Central High School in Little Rock, Ark. on September 24, 1957. Photo Credit: U.S. Army

A year after the photo was taken; Hazel married a fellow student and dropped out. She had two children when she picked up the telephone to try and track down Elizabeth. By this time the Civil Rights Movement became more violent. Racism was oozing out as fast and hard as water from fire hoses in Birmingham. Hazel was disturbed by the events. She began thinking of Elizabeth and her own actions during that time. The photograph shamed Hazel. So she called Elizabeth. “I just told her who I was – I was the girl in that picture that was yelling at her, that I was sorry, that it was a terrible thing to do and that I didn’t want my children to grow up to be like that, and I was crying,” Hazel remembered. Elizabeth forgave Hazel because she sounded sincere.

Elizabeth joined the U.S. Army and was stationed around the U.S. She rarely gave an interview about the photograph and the desegregation of Little Rock Central. Desperately, she wanted to put the past behind her. But she never could. She moved back to Little Rock permanently in May 1974. Struggling to support herself and her two sons, Elizabeth hovered over the poverty line.

Not wanting to bring up the past and everything that went with it, Elizabeth turned down interview request after interview request – even, in 1996, from Oprah. Depression pulled at her. Decades of fighting racism and those ideas that she was somehow a little less of a person because of her race, wore on her to the point that she attempted suicide twice. Elizabeth sought medical treatment. Years later she was diagnosed with Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. [She was finally able to find stability as a probation officer in 1999.] Her past, in the form of this photograph, was always there in Little Rock. Reprinted year after year, schools and textbooks used it in their study of the era. Reporters constantly hounding her about how she felt on that day.

Elizabeth Eckford and Hazel Bryan Massery at Little Rock Central High School in 1997. Will Counts Collection/Indiana University Archives

In September 1982, Elizabeth told People her life was almost non-existent and she lived “like a hermit and a recluse.” “I’ve got to get to the point where I can talk about this. Until then, it will never be over for me.” All the while, her depression hovered on the sidelines, ready to break her down at any moment. Finally, in the early 1990s, Elizabeth’s doctors found a good balance in her medicine. She began to heal.

Oprah Winfrey wanted to do a show on the Little Rock Nine in 1996. While Elizabeth declined, seven of the others come together with other students who helped them, tormented them or simply ignored them. One of the people there was Ann, who wanted to apologize. Between the Oprah Winfrey Show and other interviews, Ann discussed the reasoning behind her actions. “My parents were wonderful people, but they were also products of society,” Ann asserted. “We were all taught that you just don’t mix. We were very ignorant about segregation and integration. It wasn’t even an issue until we found out that they were going to integrate Little Rock Central High.” She often noted that she felt pressure to try and get Elizabeth to leave. “There was just a lot of electricity in the air,” she said about the day of the photograph. “It was almost a circus like atmosphere. All these parents on the sidelines urging us on and telling us ‘Get out there and don’t let them in!’”

Both Ann and Hazel expressed deep regret and sorrow for their roles and the effect it had on Elizabeth. As her children grew, Hazel taught them about black history and helped to counsel unwed black mothers. She organized field trips for underprivileged minority children. In order, some commentators argue, to right the wrongs of her past.

September of 1997 marked the 40th Anniversary of the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School. As usual whenever an anniversary of the day came around, newspapers ran the infamous photo (it had been a runner-up for the Pulitzer Prize for Photography). However, when the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette ran the photo in 1997, it also ran a current photo of Elizabeth and Hazel standing next to each other in front of the school. This time they were smiling. Will Counts again took this photo of the two. Instead of hate-filled faces with vicious words spewing forth, this photo was of acceptance and forgiveness. This was the start of an unlikely close friendship between Elizabeth and Hazel.

(Mary) Ann Thompson later in life. In 1996, she publicly apologized for her actions during the desegregation of Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Ann passed away on December 13, 2009. Photo Credit: The Joplin Globe

Of course, some people thought their new found friendship was phony. Believing Hazel was only out to get some media and clear her name, Ann remarked “I thought, ‘That little stinker! She’s doing this for Hazel, not for Elizabeth.’” Some thought Elizabeth, who forgave Hazel, was being too naive. While others thought that there was no amount of amends Hazel could do that would rid her of the stigma of the Hazel in the photograph. Ernest Green, one of the “Little Rock Nine,” added, “We kind of joked about it: here she is, framed forever with her mouth spewing out whatever she was spewing out, and no matter what she does in life she can’t erase that photo.” Green continued, “The lesson in life is: Don’t get in a picture unless you want to go through it forever, because you’re not sure which one will survive and which one will not.” Even Oprah was dumbfounded about the friendship when Elizabeth and Hazel went on her show in 1999.

The friendship did not last. It soon began to deteriorate. Not even three years passed before the two quietly parted ways. They only have talked twice since then: on September 11, 2001 and a few weeks later when Will Counts passed away. Hazel and her husband sent their condolences when Elizabeth’s son died in 2003. Of ending their friendship, Elizabeth stated it proved to be too difficult to keep going. “She wanted me to be cured and be over it and for this not to go on anymore,” Elizabeth says. “She wanted me to be less uncomfortable so that she wouldn’t feel responsible.” Hazel, opting to let the past stay where it is, withdrew from the public eye and ceased giving any interviews.

Will Count’s photograph became a real representation of Jim Crow South. It showed a 15-year-old being viciously harassed by other 15-year-olds. In reflection, it captures how hate and anger was easily be transferred by adults/parents to their children. The fear of change. The fear of the idea that, regardless of a person’s skin color, equality and freedom apply to all. The lives of Elizabeth, Hazel and Ann were forever changed on September 4, 1957. Ann, who passed away on December 13, 2009, perfectly summed up the importance of the Little Rock Nine. “I felt like Little Rock would never be the same again. We would never know life as we had known it again. Because nine people walked into a school building.”

Sources

Benjamin Fine, “Militia Sent to Little Rock; School Integration Put Off,” New York Times, September 3, 1957.

“Arkansas Troops Bar Negro Pupils; Governor Defiant,” New York Times, September 5, 1957.

John H. Fenton, “Governor Faubus Assures President He’ll Obey Integration Order, but Asks for Patience by U.S.,” New York Times, September 15, 1957.

Benjamin Fine, “President Threatens to Use U.S. Troops, Orders Rioters in Little Rock to Desist; Mob Compels 9 Negroes to Leave School,” New York Times, September 24, 1957.

Jack Raymond, “President Sends Troops to Little Rock, Federalizes Arkansas National Guard; Tells Nation He Acted to Avoid Anarchy,” New York Times, September 25, 1957.

Homer Rigart, “U.S. Troops Enforce Peace in Little Rock as Nine Negroes Return to Their Classes; President to Meet Southern Governors,” New York Times, September 26, 1957.

Homer Rigart, “Faubus Sees ‘Occupation’; Tension at School Eases; President Sets a Parley,” New York Times, September 27, 1957.

“The Oprah Winfrey Show,” January 15, 1996

Jon Anderson, “Shy Heroine Still Scarred By History,” Chicago Tribune, Oct. 17, 2000.

Juan Williams, “Daisy Bates and the Little Rock Nine,” npr.org, September 21, 2007.

David Margolick, “Through a Lens, Darkly,” Vanity Fair, September 25, 2007.

The Joplin Globe, “(Mary) Ann Thompson,” December 13, 2009.

David Margolick, “The Many Lives of Hazel Bryan,” Salon, October 11, 2011.

Louis P. Masur, “Blacks, Whites, and Grays,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, October 16, 2011.