과거의 스포츠중계 화면은 단순히 ‘보여주는 창’이었다. 하지만 지금의 중계 UI는 경기의 모든 요소를 시청자와 상호작용하는 구조로 바꾸고 있다. 화면 좌측에는 득점 상황이, 우측에는 실시간 데이터가, 하단에는 팬 커뮤니티 반응이 동시에 나타난다. 이는 단순히 정보의 나열이 아니라 ‘리듬감 있는 화면 설계’로, 사용자가 필요한 정보를 즉시 인식하도록 한다. 쿠팡플레이와 슈퍼팡티비는 이를 위해 인터랙티브 UI를 도입해 실시간 반응형 인터페이스를 구현했다.

“좋은 중계란 데이터를 숨기지 않고 자연스럽게 보여주는 디자인이다.”

한 방송 관계자의 이 말처럼, 현대 스포츠중계 UI의 핵심은 ‘투명한 정보 흐름’이다. 화면에 표시되는 모든 그래픽은 단순히 장식이 아니라, 경기의 흐름을 이해시키는 언어다.

실시간 반응형 UI – 데이터와 감정의 조화

실시간 반응형 디자인은 경기와 시청자의 감정을 동시에 다룬다. 득점 장면이 나오면 하이라이트 카드가 자동으로 열리고, 특정 선수의 이름을 클릭하면 해당 선수의 통계와 하이라이트 영상이 즉시 표시된다. 중계 인터페이스는 이제 시청자의 시선 이동을 예측하며 반응한다. 예전에는 중계가 ‘흘러가는 영상’이었다면, 지금은 ‘참여 가능한 영상’으로 바뀌었다.

UI가 바뀌면서 스포츠중계는 ‘정보 구조의 예술’이 되었다. 예를 들어, F1 중계에서는 차량 트래커와 타이어 온도 그래프가 함께 표시되고, 축구 중계에서는 전술 포메이션이 실시간으로 업데이트된다. 이런 UI는 경기 이해도를 높일 뿐 아니라, 시청자가 경기의 흐름을 읽는 능력까지 키워준다.

사용자 맞춤형 인터페이스의 등장

AI 기반 맞춤형 UI는 2025년 중계의 가장 큰 변화다. 시청자가 특정 팀이나 선수를 즐겨본다면, 인터페이스는 자동으로 해당 데이터 영역을 강조한다. 농구 중계에서는 자신이 좋아하는 선수의 슛 성공률을 고정 표시할 수 있고, 야구에서는 타자의 타석별 OPS 변화 그래프를 실시간으로 볼 수 있다. 즉, 같은 스포츠경기라도 ‘시청자마다 다른 화면’을 경험하게 된다.

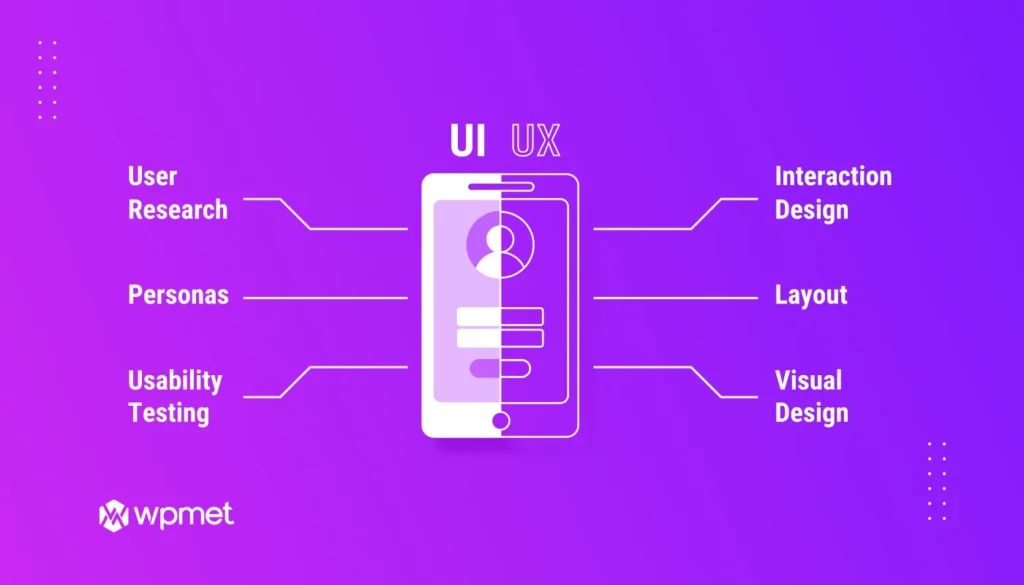

인터랙티브 중계의 UX 설계 원칙

스포츠중계 UI 설계에는 세 가지 원칙이 있다.

- 정보는 최소 단위로 나누어 한눈에 인식되게

- 감정선은 인터랙션으로 자연스럽게 유지되게

- 화면 이동 없이 모든 데이터에 접근 가능하게

이 원칙을 충실히 지킨 플랫폼이 바로 슈퍼팡티비다. 실시간 반응형 카드와 제스처 기반 조작이 가능해 경기 중에도 분석 화면을 손쉽게 열 수 있다. SPOTV NOW는 ‘데이터 축소 모드’를 통해 모바일에서도 경기 몰입감을 유지하도록 설계되었다.

시청자의 반응이 중계를 완성한다

2025년 중계 플랫폼의 차별점은 시청자 반응이 데이터로 환원된다는 점이다. 좋아요, 댓글, 채팅 반응은 실시간 그래픽으로 변환되어 중계 그래프에 반영된다. 즉, 시청자의 감정이 중계 인터페이스의 일부로 작동한다. 스포츠는 더 이상 일방적인 전달이 아니라, 실시간 협업 콘텐츠가 된 셈이다.

중계 디자인은 스포츠의 또 다른 언어

UI는 이제 단순한 기술이 아니라 스포츠의 언어다. 어떤 정보를 먼저 보여줄지, 어떤 감정을 전달할지, 이것이 중계 경험의 완성도를 좌우한다. 스포츠중계의 UI는 데이터와 감정, 그리고 시청자의 참여로 완성되는 ‘하나의 이야기’가 되었고, 그 중심에는 반응형 디자인이 있다.